Introduction

Microsoft introduced recently a new mitigation in the Windows kernel, dubbed “Component Filter”. The following blog post will explains what this mitigation is about, and how it actually works. Let’s dive in.

The big picture

Before going into the details of this new mitigation, I thought it would be better to present my own view of the aims of this new mitigation, and how it integrates with the current state of Windows’s kernel security policy. Hopefully, this is accurate enough, even if I’ll make some simplifications. People who just want technical details could go to the next paragraph.

This new mitigation is a new syscall disabling mechanism, but only for “components” of the windows kernel. Let’s see what that means:

Historically, Windows promoted a programming paradigm for userland programs based on APIs, and not on syscalls. What this means is that Microsoft considered that syscalls are not something a standard userland program should do directly, and instead, those programs should use the programmatic Windows API. It implies that syscalls can be changed between multiple Windows releases (it’s still the case), and that Microsoft is entirely in control of this mechanism. It also implies that the Windows API is fixed, otherwise all the code relying on it has to change between Windows releases. That’s why we are seeing differently numbered APIs when changes are introduced (have a look for example at GetTempPathA and GetTempPath2A). On the contrary, Linux has a programming paradigm based on syscalls. This means syscalls are fixed, but the API is not. This explains the existence of the dup2 syscall to replace the dup one.

This programming paradigm explains partly why Microsoft has not implemented any correct syscall filtering mechanism : those are not fixed! So, to provide some protection against malicious syscalls, Microsoft decided to implement a mechanism based on the disablement of syscalls given their underlying treating component. But what’s a treating component? It’s the module responsible to handle a given syscall in kernel land.

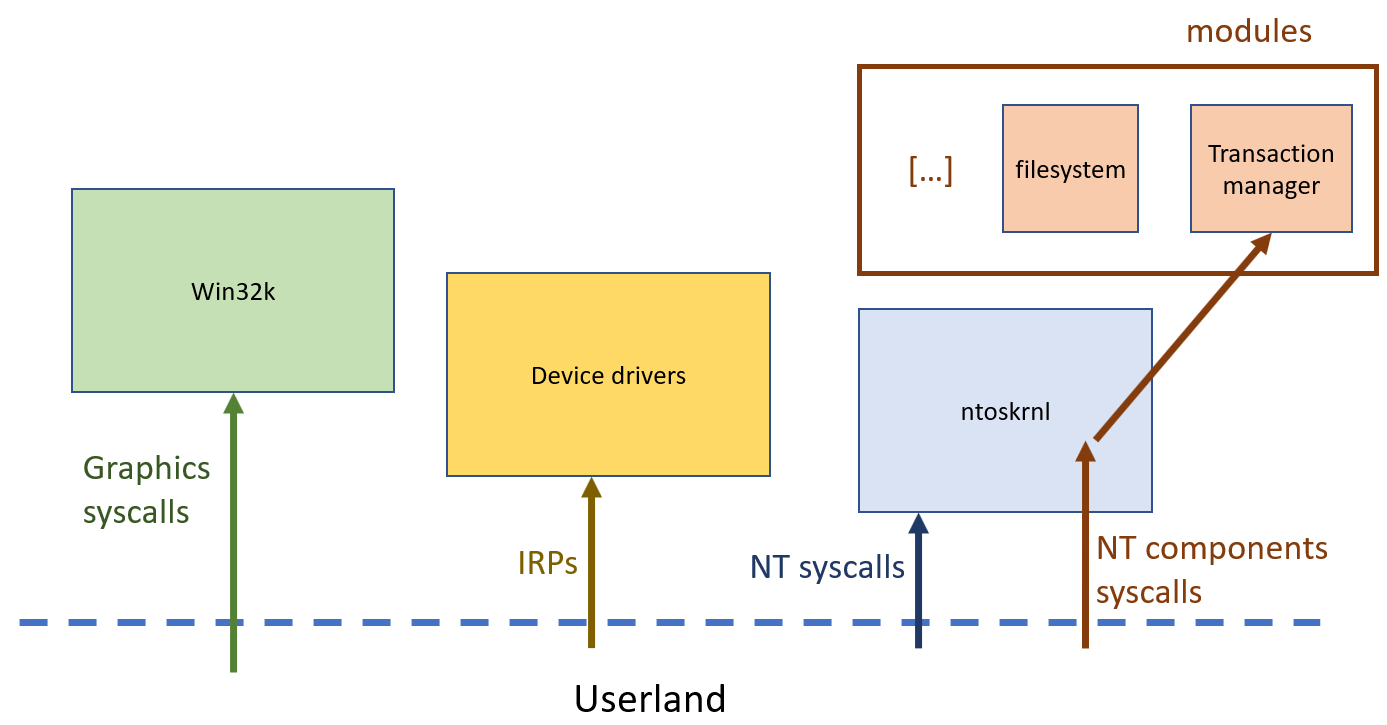

For example, one could see Windows syscalls as divided in 4 big categories:

- the graphic syscalls, handled by the win32k.sys component

- the device syscalls (in fact IRPs passed through DeviceIoControl), handled by the corresponding device driver components

- the direct NT syscalls, directly handled by the kernel

- the indirect NT syscalls, which are dispatched by the kernel to some underlying components. Examples of such underlying components are the ones handling file systems operations : depending on the file system you use, you load the corresponding component. When you want to write a file, you use the same syscall whatever is the underlying file system; it is then dispatched to the correct component able to translate it to an appropriate operation for the file system.

Here is a little schema resuming that:

Microsoft first provided the win32k lockdown mechanism. Without going into details, based on a flag defined in the EPROCESS structure, a win32k syscall is not handled by the same function.

This new component filter mitigation follows the same principle, but with more details : it will prevent transaction manager related syscalls that are dispatched towards the kernel transaction manager(KTM) component.

How it works internally

For this new mitigation to be operational, Microsoft implemented a new DisabledComponentFlags field in the EPROCESS structure. This field is an unsigned long and gets filled by the PspApplyComponentFilterOptions function. This function is called by the internal function PspAllocateProcess, and as such this new field can only get set when a process is spawned. The only way I found to define this field is through the usage of the STARTUPINFO attributes, through the UpdateProcThreadAttribute function.

This DisabledComponentFlags gets checked by a new introduced function dubbed PsIsComponentEnabled in ntoskrnl. Here is its code:

1

2

3

4

BOOL PsIsComponentEnabled(ULONG value)

{

return (PsGetCurrentProcess()->DisabledComponentFlags == value);

}

The only component using this function is the tm.sys driver, which is the implementation of KTM. Inside this driver, the following functions are now using this PsIsComponentEnabled function :

- NtCreateTransactionManagerExt

- NtOpenTransactionManagerExt

- NtQueryInformationTransactionManagerExt

- NtRecoverTransactionManagerExt

- NtRenameTransactionManagerExt

- NtRollforwardTransactionManagerExt

- NtSetinformationTransactionManagerExt

For all those functions the check related to the component is done at the beginning and is used like the following:

1

2

if ( !PsIsComponentEnabled(COMPONENT_TRANSACTION_MANAGER /* == 1*/) )

return 0xC0000022;

Using this new mitigation

As said before, you have to use the UpdateProcThreadAttribute function to actually spawn a process with this new mitigation. Here is a code to do so:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

STARTUPINFOEXA si;

PROCESS_INFORMATION pi;

SIZE_T size = 0;

BOOL ret;

ZeroMemory(&si, sizeof(si));

si.StartupInfo.cb = sizeof(STARTUPINFOEXA);

si.StartupInfo.dwFlags = EXTENDED_STARTUPINFO_PRESENT;

// Get the size of our PROC_THREAD_ATTRIBUTE_LIST to be allocated

InitializeProcThreadAttributeList(NULL, 1, 0, &size);

// Allocate memory for PROC_THREAD_ATTRIBUTE_LIST

si.lpAttributeList = (LPPROC_THREAD_ATTRIBUTE_LIST)HeapAlloc(

GetProcessHeap(),

0,

size);

//initialize the component filter

COMPONENT_FILTER cf;

cf.ComponentFlags = 1;

//create an attribute with a component filter structure

UpdateProcThreadAttribute(si.lpAttributeList, 0, PROC_THREAD_ATTRIBUTE_COMPONENT_FILTER, &cf, sizeof(cf), NULL, NULL);

// Finally, create the process

ret = CreateProcessA(

NULL,

(LPSTR) "<command>",

NULL,

NULL,

TRUE,

EXTENDED_STARTUPINFO_PRESENT,

NULL,

NULL,

&si,

&pi);

Once one of your process is spawned with this mitigation, you could try to create a volatile transaction manager with the following snippet, and see it fails:

1

CreateTransactionManager(NULL, NULL, TRANSACTION_MANAGER_VOLATILE, TRANSACTION_MANAGER_COMMIT_DEFAULT);

Conclusion

This new mitigation is actually a way to prevent 7 syscalls to be called within a process. Because there is no way to activate this feature outside of spawning a process with an additionnal attribute, this feature seems reserved for sandbox developers for now. As such, this mitigation is clearly niche.

However, because the field associated with this mitigation is not fully used, I’m pretty sure we will see additional components to be filtered in the same way, especially file systems components like ntfs.sys or nfs.sys.

Hopes for the future

As a defender, I’m baffled by the level of syscall filtering achieved by Linux with seccomp and seccomp-bpf, and the current level of the same feature on Windows. Especially, without going into a complete filtering mechanism capable of inspecting arguments passed to syscalls, Microsoft already has all the mechanisms to provide a correct syscall disabling feature inside the kernel, named “token privileges”. Indeed, when you look at what those privileges do, they are in fact preventing the usage of given syscalls! So, I would really appreciate if someone from Microsoft could state on the following system and if it’s planned to implement something similar or not in future.

Here is how I imagine a global syscall disabling mechanism can take place (based on how token privileges work):

At the spawn of a process, you create two bitmaps inside the EPROCESS structure in place of current token privileges:

- a bitmap defining the syscalls that can be activated by the said process

- a bitmap defining the syscalls effectively enabled for the said process

Basically, the first bitmap serves as the same field of the Present field of the _SEP_TOKEN_PRIVILEGES while the second one serves as the Enabled field.

The first bitmap can be created based on the following factors:

- the integrity level of the process

- if the process is signed by Microsoft or a trusted party

- if the process is created in special environments like Silo or AppContainers with capabilities

The second bitmap is created by copying the first one and updated with:

- additional attributes given by

UpdateProcThreadAttribute. - process mitigations defined

Like token privileges, you then offer the ability to disable additional syscalls, but not the ability to activate ones that are not available inside the first bitmap.

You finally just need a little checker inside the KiServiceInternal function which is the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

//I consider _EPROCESS->bitmapSyscallsEnabled to be a uint64_t*

#define IS_SYSCALL_DISABLED(A,k) ((A[(k)/64] & (1<<((k)%64)))) == 0

if(IS_SYSCALL_DISABLED(_EPROCESS->bitmapSyscallsEnabled, <syscall number>)

return 0xc0000022;

[...]

With such a system, you have so :

- a wider scope for syscall disabling than currently implemented systems

- one system instead of multiple ones : easier maintenance (merge of component filter, win32k lockdown, SpAccessCheck and PspIsInSilo functions) and vulnerability management

- the possibility to have a finer grain on syscall disabling in order to provide automatic barriers between the different integrity levels (based on the integrity level, some syscalls will be automatically disabled).

Of course, this system poses a question about performance. Microsoft certainly also chose the current implementation to support corner cases that I’m not aware about. This would also require to deprecate functions reasoning about token privileges.

To finish, I would say this system could not be complete without transforming all the “enum-based” syscalls (like the NtQuery and NtSet syscalls) into unitary syscalls. A simple example are the kernel leaks offered by the NtQuerySystemInformation function : those are actively used to achieve local privilege escalations from medium integrity, but they are all now under the same syscall.