Short Intro and past references

For a course I teach, I wanted to present the modern mitigations one can encounter on Windows. I focused on those aimed at preventing shellcode execution and ROP, because this course was on stack buffer overflows. Namely, the interesting ones are:

- Stackpivot

- CallerCheck

- SimExec

- Import Address Filtering (IAF)

- Export Address Filtering (EAF)

One of my students asked me how those mitigations really work. While Microsoft explains quite extensively its mitigations within this document, their internals are still quite obscure.

Moreover, past references that go into details appear to be quite outdated, as they were principally referencing EMET, which is now deprecated. For exemple, at that time, EMET was using hardware breakpoints instead of guard pages:

- Using EMET to disable EMET by A. Alsaheel and R. Pande

- BYPASSING EMET 4.1 by Jared DeMott

- Disarming EMET 5 52 by Niels Warnars

Recent ones are not that useful : one can find a 2019 paper on science direct, presenting a bypass of EAF by removing guard pages. This paper does not go into details either. The best bet is finally the documentation of the ETW related to Microsoft’s exploit guard done by Palantir. Some of the events like EAF are quite detailed, but for others like IAF, there is not much of an explanation.

In the end, I was not able to explain in detail how those mitigations work under the hood…

Let’s try to fill this gap: the following blog post will try to present the internals of “Import Address Filtering”, and how it should (or not) be used. It assumes the reader is familiar with how binaries are executed (virtual address space and libraries). PE format knowledge is a plus.

This blog post is the result of some reverse-engineering sessions of the PayloadRestrictions dll found inside System32, on a Windows 10. As such, following results are prone to interpretation errors. Don’t hesitate to correct me if I’m wrong.

an IAF primer

Purpose

When exploiting a vulnerable target, the attacker often hijacks the control flow of the application to redirect it to code that is profitable to him. However, most of the time, the vulnerable application does not ship the code the attacker wants to be executed. To circumvent this, the attacker often relies on injecting raw executable code, in the form of shellcode, to execute the wanted code in the context of the vulnerable application.

Like any code, shellcodes often rely on using standard library functions available on the system : it reduces their complexity and size. To call those standard functions, the shellcode needs to know their addresses in the virtual address space of the vulnerable program. For a legitimate binary, the binary loader will iterate over all the functions the binary uses, load the appropriated Dlls inside the address space of the program, and will fill a table inside the binary containing all the addresses of the functions it needs. Then, the legitimate binary just has to lookup this table to call any function. Because the shellcode is injected by the attacker and not loaded legitimately by the operating system, it has no such table containing the necessary addresses filled up automatically by the binary loader. The shellcode has so to resolve by itself the addresses of the functions it needs.

One way for a shellcode to resolve the functions’ addresses by itself is to access a known structure, known as the InMemoryOrderModuleList. This structure contains a list of all modules (Dlls+main program) loaded inside the address space of a program, with their name and base address. With this information, the shellcode is able to parse the Dlls in memory to access the list of their exported functions, and with that, their addresses. To avoid such a resolution of the addresses by a shellcode, Windows implemented a first mitigation known as “Export address Filtering”(EAF).

To circumvent this mitigation, attackers started to use another way to resolve the functions’ addresses. Do you remember the table containing all the addresses of the functions used by a legitimate binary that is filled up by the binary loader? Instead of searching for the exported functions of the Dlls, one can search for this table, known as the imports, by parsing each module obtained through the InMemoryOrderModuleList structure (or directly from the main program). IAF purpose is to thwart such a resolution of addresses.

In the end, while most of the security mitigations attempt to prevent code execution on the machine, IAF/EAF is interesting because it assumes that code execution is already achieved. It adds as such another layer to bypass in the whole exploitation process.

Reminder on PE imports

Before going further, let’s remind ourselves how imports work for a Windows executable. The Windows format for its executables is known as the PE format. It’s first made of some headers, indicating how to read the binary. Inside these headers, one can find the data directories, which are (as their name suggest) “pointers” to directories containing defined data for the executable. One of this directory is the import directory, that contains all the structures required for the binary loader to know what Dlls to load inside the binary address space, and what functions addresses need to be resolved. Another directory is the import address table, which will contain the addresses of all the imported functions once the binary is loaded with its modules.

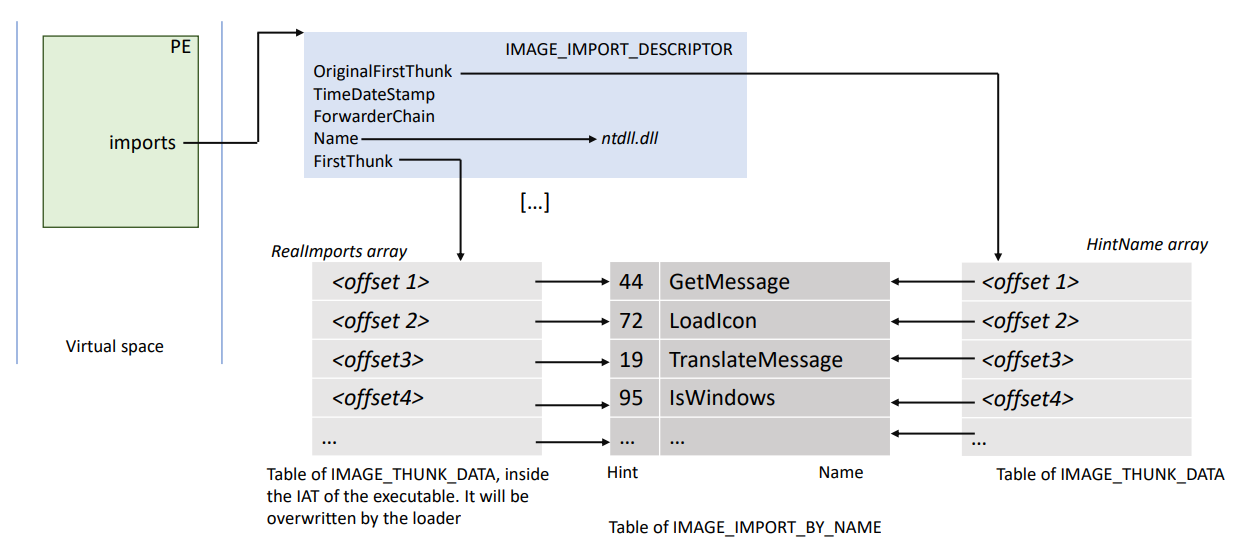

The import directory is a table of IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR structures. Each one of these permit to load a defined DLL and its associated functions. It contains the following three important fields:

- Imported Dll Name : a RVA (relative virtual address, eg an offset from the base of the program) pointing to the Dll name to be imported

- OriginalFirstThunk : a RVA pointing to a table of IMAGE_THUNK_DATA structures. We will name this table the HintName array.

- FirstThunk: a RVA pointing to an offset inside the import address table. At this offset, when the binary is not loaded, one can find the same table of IMAGE_THUNK_DATA structures than in OriginalFirstThunk. We will name this table the RealImports array. The import address table is so made up of all the RealImports arrays from each FirstThunk of each IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR.

The IMAGE_THUNK_DATA structures contain either the ordinal of the imported API or an RVA to an IMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME structure. The IMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME structure is just a WORD, followed by a string naming the imported API. The WORD value is a “hint” to the loader as to what the ordinal of the imported API might be.

Here is a schema presenting what it looks like before the binary is fully loaded:

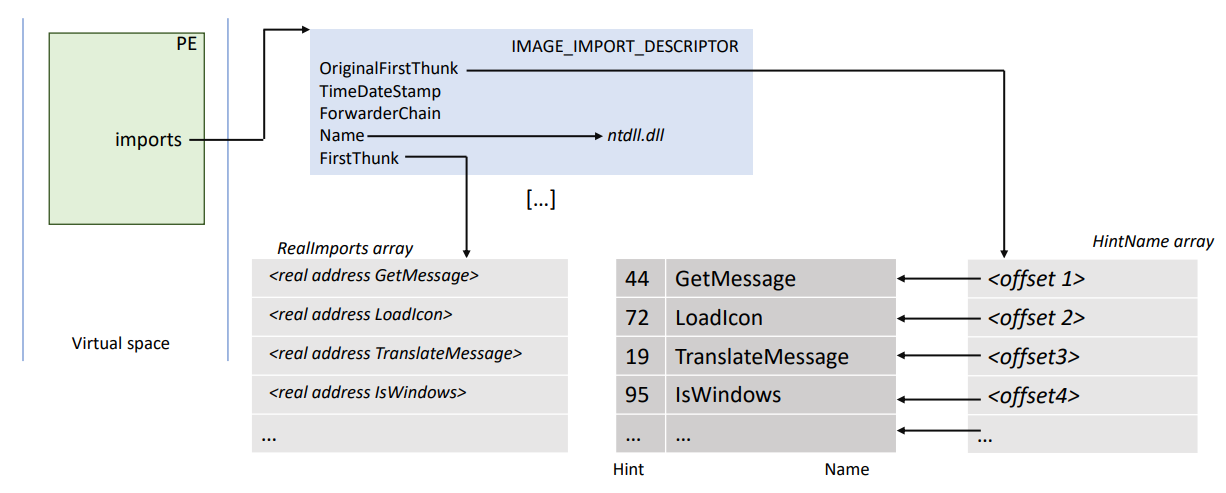

When a function is resolved by the loader, it will overwrite the associated IMAGE_THUNK_DATA inside the RealImport array with the real value of its address in the program address space. Here is what it becomes:

In the end, (for the sake of simplicity), all RealImports arrays, and as such the import address table, will contain all the addresses of all imported functions. The binary has just to call the address present at the correct offset inside the import address table to call the associated function from any Dll.

Triggering IAF

When I said that attackers can parse imports to resolve a function address inside a shellcode, here is an example C code. Once compiled, it could be used as a shellcode, resolving VirtualAlloc address in a generic manner :

uintptr_t getVirtualAllocAddress()

{

char expectedDllName[] = { 'K', 'E', 'R', 'N', 'E', 'L', '3','2','\0' };

char expectedFunctionName[] = { 'V','i','r','t','u','a','l','A','l','l','o','c','\0' };

PIMAGE_THUNK_DATA OriginalFirstThunkData, FirstThunkData;

bool found = FALSE;

//get peb

PPEB peb = (PPEB)__readgsqword(0x60);

// get the base address of our main program

uintptr_t baseProgramAddress = (uintptr_t) (peb->ImageBaseAddress);

//get the VA of the NT header

uintptr_t ntAddress = baseProgramAddress + ((PIMAGE_DOS_HEADER)baseProgramAddress)->e_lfanew;

//get the import directory

PIMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR ImportDesc = (PIMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR)(baseProgramAddress + ((PIMAGE_NT_HEADERS)ntAddress)->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_IMPORT].VirtualAddress);

// search each import descriptor to get the one corresponding to kernel32.

// this character by character method is not optimal, but easy to read

for (; ImportDesc->Name != 0; ImportDesc++) {

//first get dll Name within the import descriptor

char* DllName = (char*)(baseProgramAddress + ImportDesc->Name);

//next check if this is the correct one

int i = 0;

for (i = 0; i < 8; i++) {

if (DllName[i] != expectedDllName[i])

break;

}

if (i != 8)

continue;

found = TRUE;

break;

}

//now we got the import descriptor associated with kernel32.dll, we will search virtualAlloc function inside

if (!found)

return 0;

//get the original first thunk, which will point to Hint/FunctionName

OriginalFirstThunkData = (PIMAGE_THUNK_DATA)(baseProgramAddress + ImportDesc->OriginalFirstThunk);

//get the first thunk, which points directly to the IAT

FirstThunkData = (PIMAGE_THUNK_DATA)(baseProgramAddress + ImportDesc->FirstThunk);

//searching for virtualAlloc function

found = FALSE;

for (;OriginalFirstThunkData->u1.AddressOfData != 0; OriginalFirstThunkData++, FirstThunkData++)

{

char* FunctionName = (char*)(baseProgramAddress + OriginalFirstThunkData->u1.AddressOfData + 2);

int i = 0;

for (i = 0; i < 13; i++) {

if (FunctionName[i] != expectedFunctionName[i])

break;

}

if (i != 13)

continue;

found = TRUE;

break;

}

if (!found)

return 0;

//now we have the address of the VirtualAlloc function inside the IAT

uintptr_t VirtualAllocAddress = (uintptr_t)(FirstThunkData->u1.AddressOfData);

return VirtualAllocAddress;

}

The idea is to get the list of IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR structures, get the one associated with kernel32.dll. We then iterate over the HintName array until we find the VirtualAlloc function. The index in this table gives as such the corresponding index inside the RealImports array, where we will find the VirtualAlloc address.

We can now allocate a RWX region, copy our shellcode inside, and check that IAF is triggered (if set on the binary). An example project is given inside the trigger_IAF subdirectory.

First security observations on IAF

The first thing to note is that IAF should be used in conjonction with EAF for it to be effective. If an attacker knows you’re using IAF without EAF, he can use the “exports way” to get the addresses for his shellcode. The opposite is also true.

The other thing to note is that IAF/EAF is only useful for applications processing external data, meaning the attacker is in a remote code execution context for his exploitation attempt. Such applications may be browsers, pdf readers, office-like applications, http servers. Indeed, Windows init DLLs are mapped at the same address within each process’s virtual address space (for performance and optimisations concerns). In a local context (for example local privilege escalation), an attacker can so first run a binary normally (the binary will be considered legitimate in regards to IAF/EAF), where this binary will obtain all the necessary addresses for a shellcode. The attacker can then craft its shellcode with the previously obtained addresses, and inject it into the vulnerable program with the exploit. Because all functions’ addresses were known prior to the execution, no resolution is required, and IAF/EAF cannot trigger.

Let’s now dissect IAF and see how it works.

IAF internals

IAF setup

IAF is setup in 4 steps:

-

First, the entry point of the application is hooked using Detours API. The target function that gets called with this hook is

MitLibHooksDispatcher. The idea of this hook is to activate the IAF mitigation only once the process and its modules are fully loaded in memory. -

One page of memory (size = 0x1000) is allocated within the virtual address space of the program. We will call this memory the IAFShadowmemory. Inside this page is constructed a fake array of IMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME structures, where Hint is always set to 0, with the following function names:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

- GetProcAddress - GetProcAddressForCaller - LoadLibraryA - LoadLibraryExA - LoadLibraryW - LoadLibraryExW - LdrGetProcedureAddress - LdrGetProcedureAddressEx - LdrGetProcedureAddressForCaller - LdrLoadDll - VirtualProtect - VirtualProtectEx - VirtualAlloc - VirtualAllocEx - NtAllocateVirtualMemory - NtProtectVirtualMemory - CreateProcessA - CreateProcessW - WinExec - CreateProcessAsUserA - CreateProcessAsUserW - GetModuleHandleA - GetModuleHandleW - RtlDecodePointer - DecodePointer

For the rest of this post, this function list will be called IafApiList.

-

Whenever a module is loaded (obtained through the LdrDllNotificationCallback) - and automatically for the following dlls: kernelbase, kernel32, ucrtbase, payloadrestrictions and verifier - the function

MitLibIAFProtectModuleis called.This function iterates over all the imports of the module : if the imported function’s name matches one of the IafApiList, then the RVA of the given function’s IMAGE_THUNK_DATA inside the Hintname array is modified with the RVA of the corresponding IMAGE_IMPORT_BY_NAME inside the IAFShadowMemory.

Here is a schema indicating what it looks like:

-

When the entry point of the application is reached, due to the hook, the function

MitLibActivateProtectionsis called. This function sets up a new ExceptionHandler (that will be used to catch accesses to guard pages), ensures all memory locations within modules that should be set with PAGE_GUARD right are set correspondingly (primarily used by EAF), and finally it sets the memory rights of the IAFShadowMemory to PAGE_GUARD|READ_ONLY.

IAF processing

When a guard page is accessed, an exception is generated. With the previously set exception handler, MitLibExceptionHandler is called.

The code for this function is really simple and could be written as such:

DWORD MitLibExceptionHandler(_EXCEPTION_POINTERS *ExceptionInfo)

{

if(!g_MitLibState.IsExceptionHandlerSet) (1)

return 0;

DWORD ExceptionCode = ExceptionInfo->ExceptionRecord->ExceptionCode;

switch(ExceptionCode)

{

if(STATUS_GUARD_PAGE_VIOLATION == ExceptionCode){

return MitLibValidateAccessToProtectedPage(ExceptionInfo->ExceptionRecord, ExceptionInfo->ContextRecord);

} else if (STATUS_SINGLE_STEP == ExceptionCode) {

return MitLibHandleSingleStepException();

} else {

return 0; //exception not handled

}

}

The MitLibValidateAccessToProtectedPage function is the one of interest. It does the following: it first checks if the address guarded from the exception is inside the IAFShadowMemory. If yes, it calls MitLibProcessIAFGuardPage. Otherwise (meaning we are in one EAF guard page), it does other checks. I will name this last part MitLibProcessEAFGuardPage, and that will be potentially presented in another post.

The MitLibProcessIAFGuardPage does the following three checks:

- It checks first if the instruction pointer who raised exception is inside a memory module, by using

RtlPcToFileHeaderfunction. -

If this is the case, the list of EAFplus only protected modules (e.g. mshtml or jscript9 but not kernel32, kernelbase or ntdll) is iterated over : if this is the module who raised the exception, the function

MitLibMemReaderGadgetCheckis called. At the end, it is checked if this function has not detected any memory reader gadget.This function works like so:

- it disassembles the instruction that generated the exception

- it makes several checks on the disassembled instruction. Especially, it will be considered a gadget if:

- the instruction opcode is either a

mov,movsx,movsxdormovzx - the second operand of the operation is a memory access (e.g using

[<value>]) - the second operand validates several obscure underlying checks for which I don’t understand the logic.

Indeed, due to these last obscure underlying checks, the following type of instructions will be considered gadgets:

1 2 3

mov <register>, [ <register> + <scale> * <register>] mov <register>, [ <register> ] mov <register>, [ <register> + <scale> * <register> + <displacement> ]

While these ones will not:

1

mov <register>, [ <register> + <displacement> ]

- the instruction opcode is either a

- Finally, it checks if the stack pointer is comprised between the boundaries of the declared stack for the current thread (eg. between NtTib.StackBase and NtTib.StackLimit)

If any of these check fails, an IAF violation error is reported. Finally, if the mitigation is not in audit mode, then a __fastfail() is triggered.

if all checks passed, then the execution is passed in single-step mode through the activation of the trap flag inside RFLAGS. On the next instruction executed, a STATUS_SINGLE_STEP exception is so raised, that will be catched by our handler, and MitLibHandleSingleStepException will reset the PAGE_GUARD right.

A better IAF state-of-security as a mitigation

Knowing how IAF works internally, we are now able to state deeper on the efficiency of IAF as a mitigation for remote exploitations :

-

IAF tries to block only API names resolution. There is no protection on IAT per se.

-

If an attacker is able to know/leak the precise version of the vulnerable binary before launching the exploitation, and has access to the corresponding binary, then IAF can be easily bypassed. Such cases are browsers, where attacks occur in two steps (as demonstrated by p0’s in-the-wild-series): a fingerprinting of the browser is made first. With this information, the appropriate exploit is then launched.

Why? Because if the attacker knows the precise version, he knows where the appropriate function address will be in the IAT of the vulnerable binary (this is fixed at compilation time). He does not have to parse the import descriptors’ OriginalFirstThunks to look out for the correct function name, and he will not trigger IAF mitigation at all.

Accessing the correct address where to find a said function can be easily done with CFF Explorer for example. Go to the “Import Directory” tab, click on “Kernel32.dll”. There are two pieces of information to get: the IAT offset and the index of the VirtualAlloc function in the OriginalFirstThunks list. With this information, the VA at which you will get the current address of VirtualAlloc is simply :

1

Base Program address + IAT offset + 8*(index of VirtualAlloc)

-

Rest the case where the remote attack occurs against a large variety of versions for the same target, and in this case the attacker is not able to retrieve the precise version of the target (we state so that the attacker is not able to retrieve the current versions of the dlls in use on the system). An attacker willing to use imports for his shellcode should:

- bypass the check on the limits of the stack. It’s kind of difficult to state on this check, because it depends entirely on the exploitation method and the primitives the attacker is able to gain. It can be really effective as well as completely useless…

- bypass the check stating that the address generating the exception is inside a defined module. For this, the idea is to use gadgets, either inside kernel32, kernelbase or ntdll; or to use gadgets from the EAFPlus modules that are of the form

mov <register>, [ <register> + <displacement> ]. Because the attacker does not know the different versions of the Dlls, he has to scan the modules for a given code pattern, or compare the versions of the Dlls against a known database of gadgets. The requirement for a successful exploitation appears higher, but it’s still something not that complicated to do. - bypass the check on memory gadgets? Simply use the same methods from the previous point.

Conclusion

The design of IAF, as well as EAF, won’t have a huge impact on performance, and as such, can certainly be used for a majority of use-cases. In the end, it appears IAF might be interesting, in conjunction with EAF/EAFPlus, to thwart attackers that did not take into account these mitigations while exploiting a vulnerable binary in a RCE context. However, if an attacker has taken into account the possibility that IAF/EAF might be activated on the remote target, then he will certainly be able to bypass it.

There seems to be no good answer as to if IAF/EAF should be enabled or not.

I would love to see an IAFPlus, with stricter checks. For example, it seems that if an application does not use LoadLibrary and does not have delay-loaded imports, one could prevent all OriginalFirstThunks access for name resolution. It would be also interesting to see some kind of IAT randomization inside the PE format to force any code trying to resolve address to first resolves names.

additional notes

(1) g_MitLibState is a globale structure defining the current state of the modern mitigations applied to the binary. It’s in fact comprised of the whole .Mrdata section inside the PayloadRestrictions dll. While this section is marked as READ_ONLY, whenever the structure needs to be filled with data, this section is passed as READWRITE by PayloadRestrictions’s functions and then passed again to READ_ONLY.

Here is the structures layout:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

struct gmitlib_module_info_struct

{

void* baseaddress;

uint32_t sizeOfimage;

uint32_t indexGuardedPageInfo;

char* moduleName;

char* modulePath;

uint32_t moduleStatus;

uint32_t isEAFPlusProtection;

};

struct gmitlib_guard_info_struct

{

uint32_t index_module;

uint32_t newProtect;

void* baseaddressAligned;

void* baseAddress;

};

struct eafplus_module_struct

{

char* moduleName;

char* Extension_if_glob;

uint64_t sizeModuleName;

};

struct gmitlib_protected_apis_struct

{

void* apiName;

uint32_t lenApiName;

uint32_t unk0;

void* encodedPointerShadowMemory;

};

/*alignment on 8*/

typedef struct

{

char unk0;

char HasIAFOrEAF;

char HasROPMitigations;

char IsExceptionHandlerSet;

char isOneModuleProtectedAgainstROP;

char IsEntrypointHooked;

uint32_t MitigationOptionsValue;

uint32_t numProtectedModules;

uint32_t numberEAFPlusModules;

uint32_t availableIndexListModifiedpages;

uint64_t indexTlsbitmap;

void* baseProgramAddress;

void* EAFPlusShadowMemoryAddr;

*void* IAFShadowMemoryAddr;

uint32_t RealSizeIAFShadowMemory;

uint64_t unk1;

HANDLE SecurityMitigationsProviderRegistrationHandle;

gmitlib_module_info_struct listProtectedModules[35]; //you can have up to 32 EAFPlus modules

gmitlib_guard_info_struct listGuardedMemoryPages[35]; //listed with ImageFileExecutionOptions

eafplus_module_struct listEAFplusModules[32]; //registry key

gmitlibdetour_struct HookedFunctions[47]; //size element = 0x28

HANDLE eventHandle0;

HANDLE eventHandle1;

void* EncodedPointerHeapEvent;

char ProgramName[520];

uint32_t sizeFullProgramName;

gmitlib_protected_apis_struct IAFProtectedApis[26];

} g_MitLibState_struct;